Syracuse University’s glassblower Sally Prasch works with science departments for 10 years

Tucked underground in the Life Sciences Complex is a shop filled with plants — dead and alive — glass projects in progress, metal machines and a fish tank.

A poster that looks like a window to the outside hangs on the wall that Sally Prasch faces while working. Written on her door is the word “welcome” in a variety of languages.

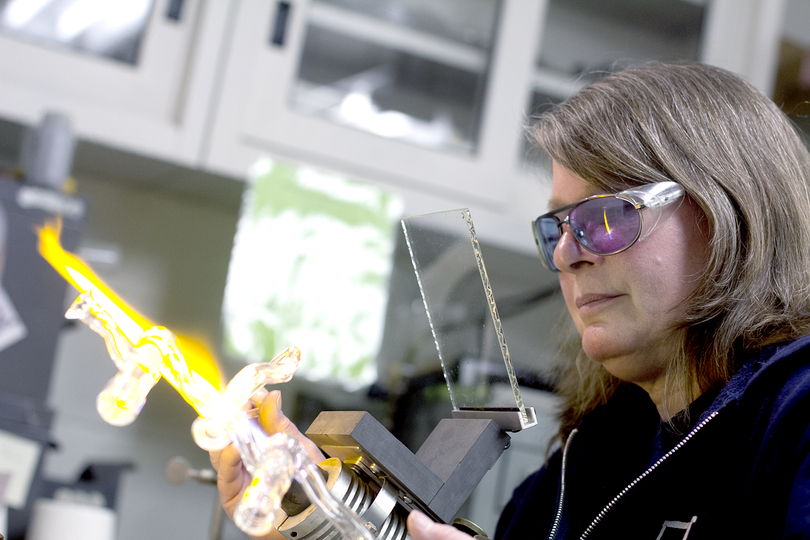

Prasch has been Syracuse University’s glass shop director and facility manager for 10 years, working closely with science departments to create, customize and repair glass science equipment. The 56-year-old uses a flame torch and pre-made glass tubing to create her projects. Her job saves the school and its students time and money that would make some of their research impractical if they had to get their glass customized and repaired elsewhere.

She is also teaching — not for credit — six students interested in glassblowing. But Prasch is as much a worldly artist as she is a science department handywoman.

“People bring me plants that are dying, and they want me to fix them,” Prasch said.

Prasch began glassblowing at age 13 when she took her first class. She was hooked, and went on to apprentice part-time with a scientific glassblower at the University of Nebraska before getting her Bachelor’s Degree in Fine Art in Glass at the University of Kansas.

One of Prasch’s favorite parts of her job at SU is facing new technical challenges daily.

When a Chinese student who spoke limited English came to her with a glass project, she took it on, only to see from the student’s face when she finished that she had misunderstood him. They ultimately worked to fix it.

Overcoming language barriers has been a constant of Prasch’s career. She’s traveled abroad to teach in Japan four times — as well as Sweden, Ireland, Italy, Germany — and is visiting Turkey for the second time this May.

In 1990, when Prasch first traveled to Japan, she had to have a full-time translator help her speak with her students. She communicated with hand motions, drawings and facial expressions — no form of communication was off limits.

“It was a blast. I loved it. When I go to another country to teach, I’m like an open book,” Prasch said. “So they have to open up to me — I’m learning their culture.”

Inside the glass shop she has a tank with two koi fish she bought after returning from Japan, named Kin and Mizutama, that are growing too big for their tank.

Prasch writes notes to them in Japanese on the outside of the tank.

“Your pond will be ready soon,” one reads, written backward, so the fish can read them.

Written inside the doorframe of her office are the names of students she’s worked with. Of her current six, most are chemistry students who want to learn more about glass, so they can perform simple adjustments and repairs to the glass they’re working with. Up to three students can work with Prasch in the glass shop at a time.

Chemistry graduate student Craig Sherwood, one of Prasch’s students, has been taking lessons from her since the beginning of this semester.

“I think she’s great. She’s very optimistic — whenever something I make looks bad she’s like, ‘Oh no that’s great!’ She’s made it very, very enjoyable,” Sherwood said.

Without her, Sherwood said, he simply wouldn’t be able to complete many of his projects.

Mario Montesdeoca, the laboratory manager of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, called Prasch “a catalyst for research.”

Montesdeoca said Prasch’s expertise is necessary because she understands certain types of glass and their effects, as well as helping students avoid making mistakes.

“She’s my 911 when I need glass to be fixed,” Montesdeoca said.

Montesdeoca’s calls are just another set of problems for Prasch to solve.

“Sometimes we come up with some really bizarre things. I’ve been working in this since 1970, and people still come up with things that I’ve never seen before,” Prasch said. “Science is changing, and as science changes the glass changes. Glass has always been a part of science.”

Prasch’s passion for glass goes beyond science, though.

She has a studio at her home in Montague, Massachusetts where she makes artistic glass projects. Prasch’s interests in art and science often intersect while she works with glass.

“I use a lot of my scientific glasswork techniques inside my artistic work,” Prasch said. “In science we put a lot of tubes inside of tubes inside of tubes, and a lot of my artwork reflects that.”

Prasch emphasized her strong belief in the value of creating, be it with glass or another medium, and that she is concerned that schools today are no longer teaching students this important skill.

“I think our society as a whole is moving away from learning how to work with your hands, and that’s very sad for me,” Prasch said. “We’re losing art and craft. It’s hard.”

Prasch pointed out that even though society knows that being well rounded helps students learn better in all subjects, artistic programs continue to be cut. She noticed that today, many students have become caught up in working toward getting a high-paying job, but are missing out on the other joys of life.

Said Prasch: “I think it’s part of your soul. I think it’s in everybody’s soul to create.”

Published on April 6, 2015 at 11:11 pm

Contact Alex: aerdekia@syr.edu